we used to say BRB. now we just live here.

thoughts on the internet as an entity & avoiding the inherent friction of human interaction

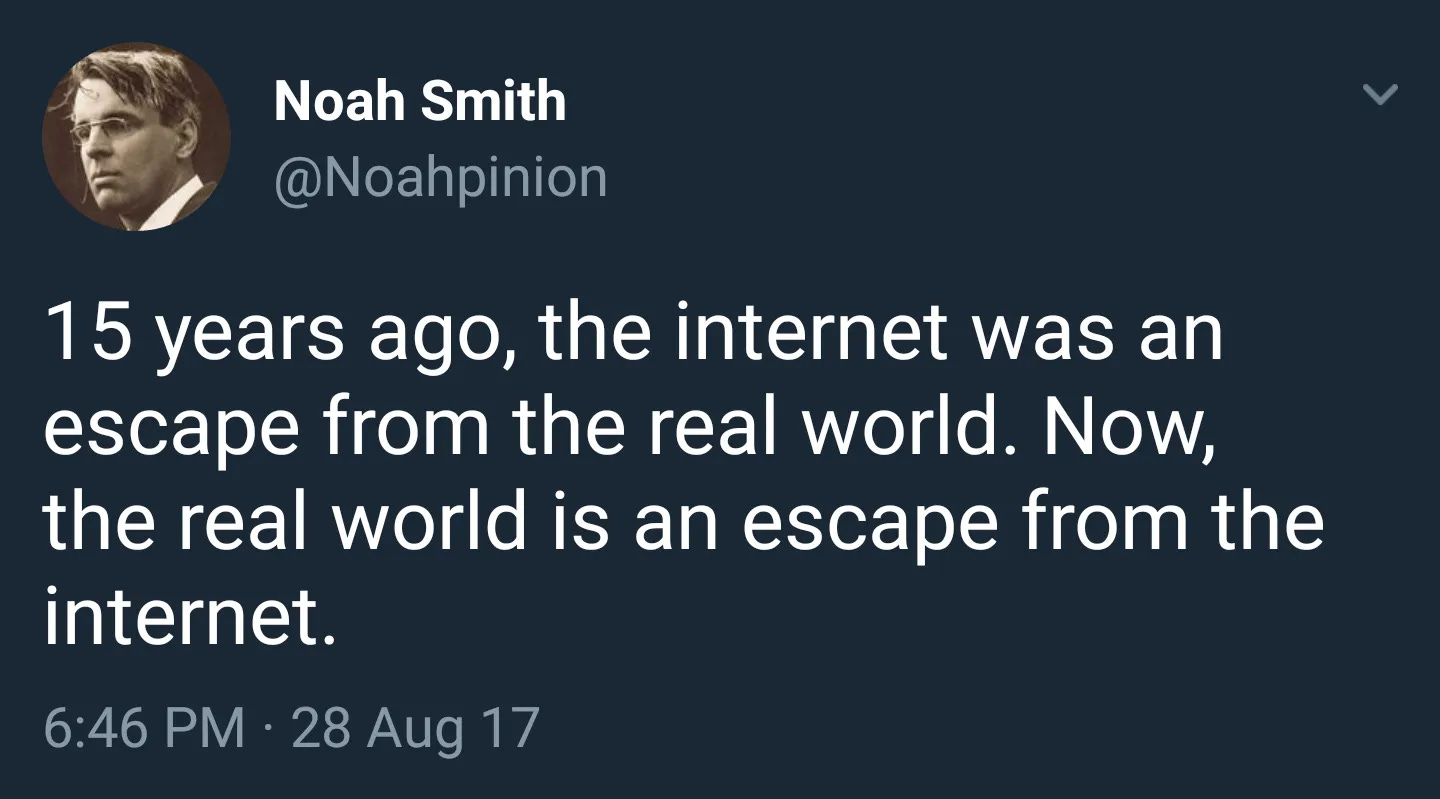

Last year, I saw this tweet…

…and I have not stopped thinking about it.

As Marshall McLuhan prophetically stated, “We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.”

We used to say BRB, but now we just live here.

I also recently read this:

While the internet is no longer one physical place, I do think of it as an entity. The internet has an undeniable presence.

It's a common and unsettling experience: you're trying to have a conversation, but the other person is more focused on their phone, making you feel like you're just talking to yourself or third-wheeling. Or being next to a friend, both engrossed in your screens, feeling as if you're hanging out with the internet itself. This shift in social engagement isn't just anecdotal; it reflects a broader change I've observed over time.

Reflecting on my earlier years, the classroom was a hub of chatter and camaraderie during breaks or in the precious minutes before and after class. Contrast that with the present, possibly a symptom of the hectic pace of graduate school, where everyone instinctively turns to their devices. This pattern extends beyond the classroom, too. It's like when you walk into a room and don't know anyone, so you whip out your phone. You're not a loser! You're connecting! Our bond with our devices has transformed into a complex, albeit misleading, sanctuary — a digital security blanket that masquerades as a tool for connection while paradoxically deepening our isolation.

Just like Sherry Turkle said, “Technology is seductive when what it offers meets our human vulnerabilities.” This seduction has not only altered our interactions but also reshaped the very nature of our communal spaces.

We used to have third places — a place outside your home or work where you can relax and hang out. Your first place is your home, a private and domestic space. Your second place is your work, a structured social experience and where you likely spend most of your time. Your third place is somewhere you can connect with others, share your thoughts and dreams, and have fun. A third place is an anchor of the community and usually a public setting that hosts frequent and informal gatherings of people. Most people are loyal to their place and return regularly to unwind and socialize. It’s best if it's located close to your home or work.

However, the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically upended these social structures. The traditional 'second place' of work was disrupted, often replaced by remote environments that blurred the lines between professional and personal spaces. Simultaneously, for many, the cherished 'third place' receded into a distant memory, a casualty of necessary isolation measures (and then became increasingly costly).

Third places hold a unique significance, offering a sanctuary from the relentless pace of daily life and granting us the mental respite essential for relaxation and rejuvenation. However, in our progressively digital era, the internet has steadily encroached upon the domain of these communal spaces. Our living spaces are also becoming increasingly integrated with smart technology and digital conveniences, which often diminishes the allure of venturing outside. Instead of going out to socialize, we’re ordering in, online shopping, binge-watching streaming services, and endlessly scrolling through social media. But these are just substitutes for authentic connection. No matter how many devices are plugged in, we’re still disconnected from real human interaction. Social media often functions as a proxy for friendship, creating an illusion of a more expansive social circle than what really exists.

Although some online communities can offer an important sense of inclusion and familiarity, they fall short compared to more traditional forms of connection. The importance of balancing our digital lives with in-person relationships cannot be overstated. This Atlantic piece titled Always Talk to Strangers highlights that people who know and trust their neighbors are less likely to experience heart attacks. Similarly, this study finds a strong correlation between social relationships and longevity, and this article cites research on how strong social connections are linked to better physical and mental health, coping skills, sleep quality, and much more. Despite this deluge of data underscoring the health benefits of community, there is often a disconnect between what we know and how we act.

Human interactions are, by their very nature, awkward and imperfect and made of friction.

Corporations selling convenience at every turn have made it all too easy for us to sidestep the very human interactions that once defined our daily lives. This reality, echoing Neil Postman's sentiment, “Technopoly eliminates alternatives to itself,” plunges us into a world where everything is streamlined and frictionless, presenting no challenges and leaving us ill-equipped to engage with the multifaceted nature of people. People, as well as the communities, relationships, and friendships they build, are complex systems that require an understanding beyond just technical fixes. They demand a nuanced understanding that balances multiple aspects of the human experience, not merely technical solutions. This dissonance is at the core of contemporary loneliness.

My generation and I have been inculcated with the fallacy that we can eradicate all forms of unease from our lives. Remote work allows us to fulfill professional obligations from the comfort of our homes. The digital dating landscape presents us with an endless parade of potential partners, yet we complain that these interactions often lack depth and substance. After spotting an outfit on TikTok, we click a link-in-bio to buy. Even grocery shopping, once a routine chore, can now be outsourced to others when the task feels too burdensome. However, this screen-centric lifestyle comes with a cost. We often find ourselves mindlessly scrolling through our phones while a TV show plays in the background, resulting in a fleeting, fragmented experience where neither the show nor the content on our phones leaves a lasting impression. In an attempt to keep pace with our diminishing attention spans, we speed through media at 1.5x, racing to consume more yet absorbing less. The simplicity and convenience of our modern lives paradoxically lead to a state of burnout, leaving us drained of the time and energy necessary to cultivate the small, unremarkable, yet profoundly significant local friendships and acquaintanceships.

So, this year, I am setting myself two challenges:

To enter rooms full of strangers without retreating to my phone. To walk in with good posture, my phone away, smile at strangers, and pay someone a compliment. I call this “having my green light on,” to signal warmth, openness and receptivity.

To replace one digital activity with its analog counterpart each week. For example, instead of applying for a library card online, I'll visit the library and get one in person from the librarian. Similarly, rather than ordering my coffee through an app, I'll order directly from the barista. I want to reconnect with the tangible, human elements of these everyday tasks.

I hope you join me.

Human interactions are awkward. They are imperfect. And they are oh-so-worth it. 💖

appreciate the tangible action takeaways at the end

this feels so hopeful to me, like a window opening to the real world